I'm telling this story backwards. In part 2, I wrote about Christopher Lardner. This time I'm writing about his mother, Ann, and her parents. Its a story of the England that Charles Dickens wrote about.

Ann was born about 1838 to a family of "agricultural laborers"--farmhands who didn't own their own farms. As you might imagine, their income was low.

Traditionally, a poor tax, collected from residents and administered by the Anglican church parishes, provided relief to poor families. It was typically confined to those who were too young, too old, or too sick to work, although there were some benefits for unemployed able-bodied persons.

Economic times were tough in rural Britain. The expanding economy created by industrialization provided no benefit to the agricultural parts of the economy, while over-production of crops reduced income and a high rural birthrate produced a surplus of labor. Furthermore, the local weaving industry was in decline. Between 1795 and 1820, the rate of the poor tax quadrupled and the taxpayers were complaining of the burden.

The solution was to form "unions" among closely located villages. A single "workhouse" would be established to house and feed the poor. It would be operated by a paid contractor, who also retained the proceeds of any production of the workhouse.

The Victorians were concerned that workhouses would breed indolence, so life there was deliberately dismal and the work was deliberately menial. If an able-bodied person entered the workhouse, he or she was required to bring the entire family. The sexes and the children were segregated. Families might meet for a few hours once a week.

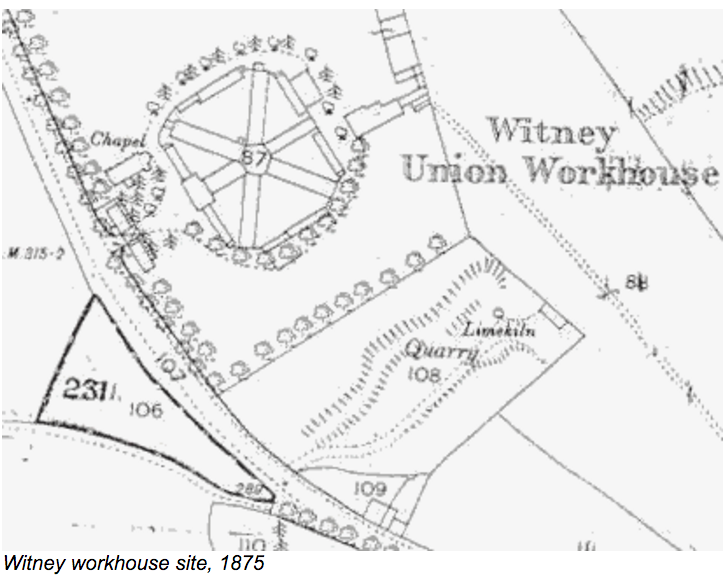

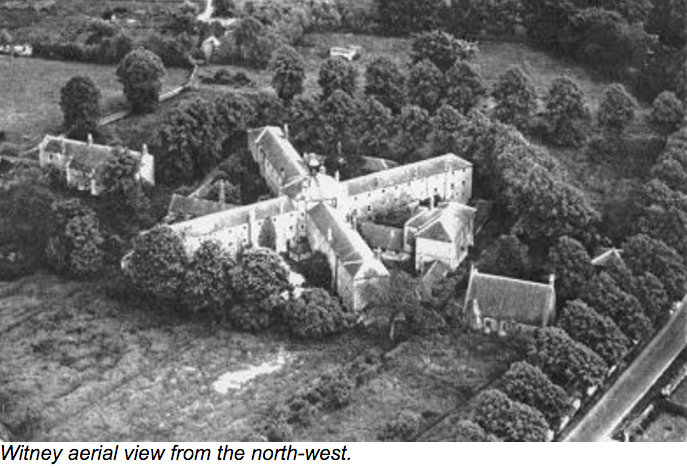

That was the situation of the William Lardner family in 1851. Forty-year-old William, his wife Elizabeth, and four children, including fourteen-year-old Ann, were "inmates" of the Witney Union Workhouse. We don't know how long they were there. The records of the workhouse have been lost; we have only the single snapshot provided by the 1851 census, but we know that the family was not resident in the workhouse during the 1841 and the 1861 censuses.

We can't be sure what kind of man William was. We know that in 1839, five years after his marriage, he and his brother-in-law were caught stealing wood, convicted of larceny, and sentenced to three months of imprisonment. Maybe he was stealing to warm his family.

Persons were free to come and go from the workhouse, when they found outside employment. Perhaps that is what Ann did. The 1861 census shows her working as the sole servant in the household of an unmarried man, James Buckingham. She had two children, and a third, Christopher, was on the way. Evidence suggests that Buckingham was the father of all three. The situation was not to remain, though. In 1865, Buckingham married Fanny Carter. Two years later, Ann died--back in the Witney Union Workhouse. In the 1871 census, her ten-year-old son, Christopher, is an orphan in the workhouse—the only Lardner listed there.

Was Ann exploited, or did she fall out with a once generous benefactor? We will never know.

Ann Lardner was a 2nd great-grandmother of the Lardner sisters. Christopher, of course, was their great-grandfather.