In 1680, Grace Swain Boulter and her daughter, Mary Prescott, were accused of witchcraft in Hampton, Massachusetts (now part of New Hampshire). By this time, many local authorities were becoming reluctant to pursue claims of witchcraft. Most still believed in the phenomenon of witchcraft but had lost confidence in their methods for separating the guilty from the innocent. The accusations against Grace and her daughter were not pursued, although two other accused women were jailed indefinitely by the means of a high bail bond.

Grace's case is far from the most dramatic instance of the epidemic of witchcraft in 17th century New England. Rather, its mundane nature invites us to examine the general characteristics of the outbreak. In the 105-year period beginning in 1620, at least 344 persons were accused of witchcraft in New England. We can ask the question — what sort of person was accused as a witch? The answer is surprising and may be particularly interesting to those interested in feminist history.

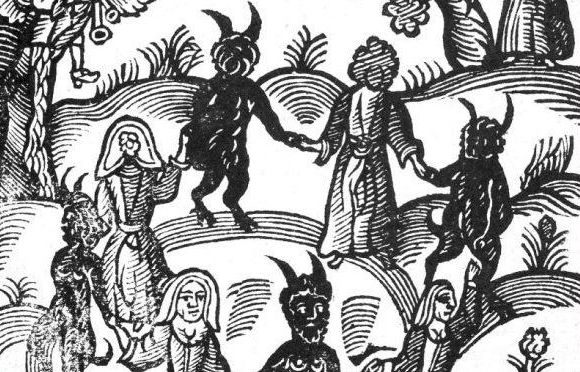

For starters, 78% of the accused New Englanders were female. Of the few males who were accused, about half were direct associates of the accused females, rather than independent actors. Are you unsurprised that they were mostly women? Well, that's because those New England prosecutions are at the root of our popular beliefs. Prior to this time, the English concept of witchcraft assumed no particular gender. Most contemporary English writers used the generic male pronoun when discussing witchcraft.

During investigation and trial testimony, it was recorded that many of the accused were unpleasant people. Anger, when expressed by a woman, was viewed with much suspicion. The term “scold” (a near-synonym for “witch” in those days) meant an angry woman; there was no corresponding word for a man. The Puritans viewed discontent as “thinking oneself above one’s place in the social order.” Discontent was a common aspect of the lives of accused witches; many were involved with petitions and lawsuits. Never mind that men used the courts extensively to settle even minor grievances.

But there's an even more surprising characteristic... More than 60% of the accused women (and more than 89% of those executed) are known to have lacked brothers and sons. What’s going on here?

To understand the relationship, it’s important to understand the Puritan notions of social hierarchy. Puritan religious doctrine had removed the priest from his position as the mediator with God, but had retained the hierarchy, with the head of each family implicitly filling that role. The wife was intended to be her husband’s “helpmeet”. The common law principle of “femme covert” prescribed that, upon marriage, "the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended.”

The family hierarchy was reinforced by both custom and common law, dictating that the property the wife brought to the marriage became her husband’s. Upon the husband’s death, the widow was provided with the use of—not ownership of—1/3 of his property to support her for the remainder of her life. The remaining property was divided among the sons and daughters. The daughters’ shares were conveyed to their husbands. A guardian was appointed to protect the property, pending distribution, of an underage male or an unmarried female.

The interlocking laws, customs, and beliefs created a stable social structure, centered on the father, with all others subordinated to him. Enlightened fathers sometimes distributed property to their children prior to death, allowing the sons to create their own hierarchical families, and the daughters to carry a dowry. Regardless, the women remained property-less and subordinated--whether to their father or to their new husbands. This hierarchy was the fundamental mechanism for enforcing the Puritan social order.

Many of the accused witches had escaped disempowerment—usually via widowhood. But, in the view of her neighbors, a woman operating outside the hierarchical family was a suspicious anomaly, executing neither of the responsibilities of women—childbirth and performing as a helpmeet. Widows were strongly encouraged, even coerced, to remarry, but some chose to remain outside the hierarchy. The ones who could afford to do that were those who, contrary to convention, had obtained the ownership of property. In many cases, they had received an inheritance themselves because they lacked brothers or sons. In a few cases, enlightened fathers or husbands had chosen to pass property directly to them, and the local magistrates had permitted the transfer. Remember that definition of discontent? —“thinking oneself above one’s place in the social order.” Perhaps the propertied women did regard themselves as being above other women or, at least, were so perceived.

Grace Swain Boulter was one of the propertied women. Twenty years before, her father Richard Swain, disenfranchised on suspicion of being a Quaker, disposing of his many Hampton properties as he fled to Nantucket, deeded a substantial portion of that property directly to Grace. At the time of the witchcraft accusation, her husband Nathaniel was within three years of his death, and Grace may very well have been carrying on his notably litigious behavior, thus operating outside the accepted role boundaries of women, and implicitly threatening the stability of the Puritan hierarchy in her community.

- - -

Grace Swain Boulter was the step-daughter of Jane Elizabeth Godfrey Swain, a ninth great-grandmother of the Moore brothers.

A seventh great-grandmother, Hannah Griswold, was also accused of witchcraft in Saybrook, Connecticut. She was the wife of a prosperous man. Although this was not always an effective protection, the charge in her case was not taken seriously.

- - -

Most of the information in this article comes from:

Karlsen, Carol F.. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England. 2013 Kindle edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1998. The book is the published version of her PhD dissertation.