My 5x great-grandfather Thomas Manchester and his son, John, served in the “Sea-Coast Defense” of Martha’s Vineyard during the Revolutionary War.

Like the rest of Massachusetts, Martha’s Vineyard was on edge in the days leading up to the Revolution. As early as October 1774, the towns formed a committee to discourage trade with Britain, vowing, in their words, “non-importation, non-exportation & non-consumption.” In the early months of 1775, the towns formed Committees of Safety and started sending their tax revenue to the Massachusetts provincial congress rather than to British authorities.

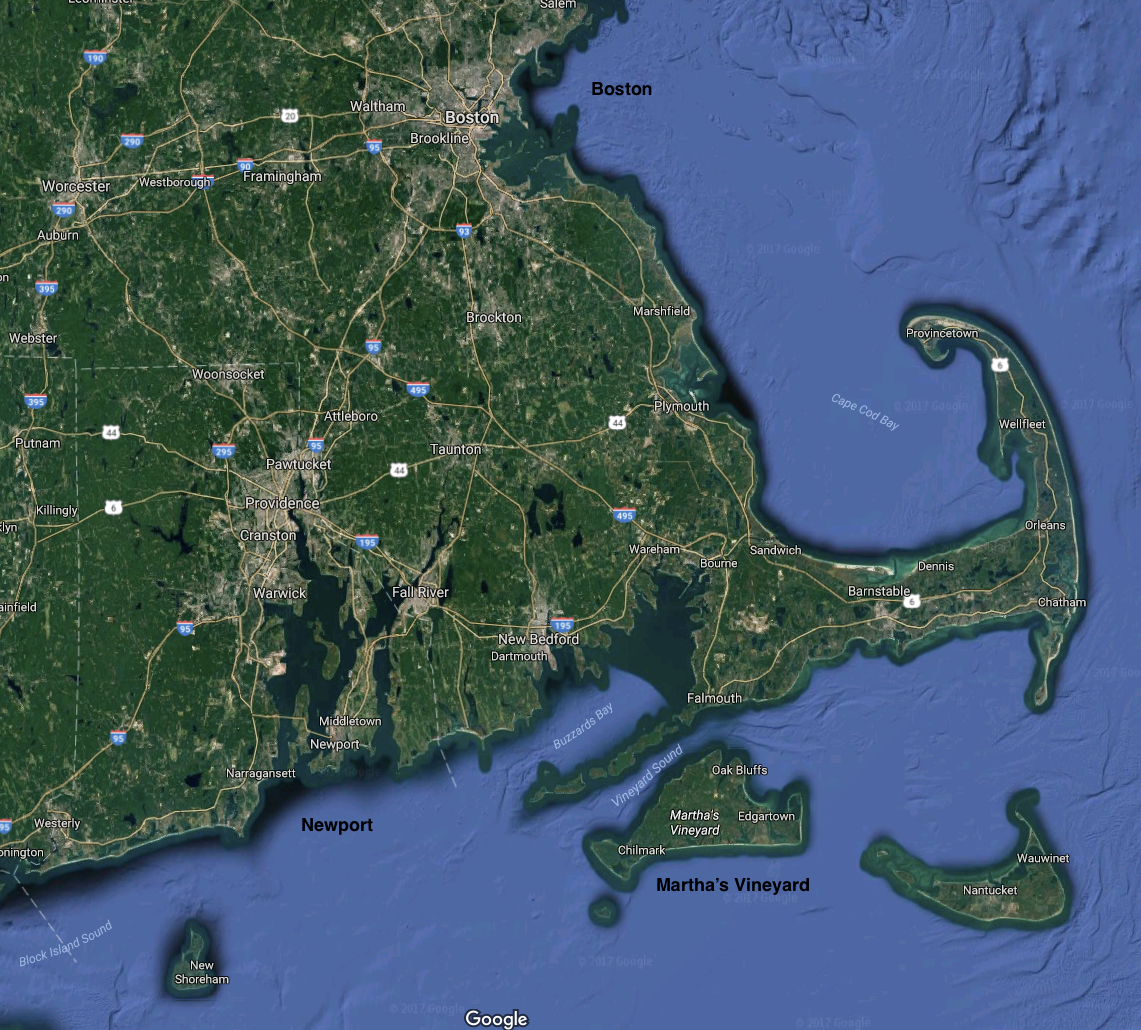

After hostilities began on April 19, the British fleet began to harass outlying communities with coastal raids using the Vineyard Sound as their base of operations. One armed sloop took 13 prize ships during a 20-day period in May. The population of Martha’s Vineyard (as counted a year later) was only 2881, scattered around the island, insufficient for effective defense.

By the end of 1775, Massachusetts had authorized the creation of a force for Sea-Coast Defense. Two companies totaling about 120 men were formed by spring 1776. A third company was formed on the mainland and dispatched to the island. By July of 1776, a total force of 250 men in Sea-Coast Defense, augmented by a similar number of militia, would have sufficed to repel any landing party of the British fleet. However, the records show no action and only a single alert during the remainder of the year.

The lack of activity does not imply that the British were awed by the defense force. Actually they had effectively abandoned New England after having been expelled from Boston in March. The Massachusetts government began to perceive the Sea-Coast Defense as being a substantial expense with no accompanying benefit. Furthermore, as the year wore on and the Continental Army suffered disastrous defeats at Long Island and Harlem, and was pushed out of New York, it became clear that soldiers were needed elsewhere.

In November 1776, the Massachusetts government drastically reduced the Sea-Coast Defense to only 25 men. Many of the discharged men joined mainland companies of the Army or became privateers. Ironically this reduction occurred just as the British were occupying Newport. The islanders requested that the defense force be reinstated. The Massachusetts government reacted in March 1777 by abandoning the defense of the island. They recommended that livestock be removed to the mainland and directed that the inhabitants should not resist the enemy if attacked. In April 1778, they further directed the island’s militia commander, Col. Beriah Norton, to deliver all ammunition stored on the island to the mainland forces.

Thus, the island was left to its own devices when the British, in support of their Newport operation, commenced naval raids on the southeastern coast of New England. On September 10, 1778, a fleet of a dozen warships, scores of transports, and 4,000 soldiers arrived at Martha’s Vineyard. An agreement was reached that the locals would surrender their arms, turn over any public funds, and provide 300 oxen and 10,000 sheep, in return for compensation. Apparently, the islanders slow-rolled the operation and two days later, frustrated by the delays, the fleet’s commander Sir Charles Grey (and his adjutant, the infamous Major John Andre) dispatched his soldiers to force compliance — resulting in looting, the destruction of 27 boats and the salt works, and one fatality. The tally kept by the islanders counted 388 weapons, 315 cattle, 10,574 sheep, 52 tons of hay, and about 1000 pounds sterling delivered to the British.

The Vineyard saw but little of the remaining war. Occasionally a warship or supply ship would founder on the reefs. Occasionally a warship or privateer would conduct a small raid for livestock.

Incredibly, for 10 years, during and after the war, including two trips to Britain by Col. Beriah Norton, the Island pursued its claim for the promised repayment, but with no satisfaction.

- - -

Thomas Manchester, the 5x great-grandfather of the Moore brothers, and his son, John Manchester, were privates in the Sea-Coast Defense forces.

Col. Beriah Norton, the commander of the island’s militia, was a first cousin 7 times removed.

Roughly 20% of the Sea-Coast Defense forces, the island’s militia, and the islands leaders were named Bunker, Cottle, Daggett, Dunham, Hatch, Look, Mayhew, or Norton, and are probable cousins (6 or so generations removed).

The primary source for this article is:

Banks, Charles Edward. The History of Martha’s Vineyard, Dukes County Massachusetts. 3 volumes. Boston: George H Dean, 1911. Volume 1, General History, and Volume 3, Family Genealogies.

The map is from maps.google.com.