In 1647, a group of followers of George Fox, an Anglican churchwarden’s son, formed the Religious Society of Friends, devoting themselves to Christianity in its original simplicity. Fox openly criticized the established church and the injustice that he perceived. In 1650, a judge imprisoned Fox for blasphemy, mocking his exhortation to “tremble at the word of the Lord,” by calling him a “Quaker.” The new religion spread rapidly; by 1657 about a thousand Friends were in English prisons.[1]

In the New World, like England, the Quakers raised “an accusing and critical voice”; and, like the Anglican leaders against whom they were revolting, the Puritan leaders in Massachusetts perceived the Quakers as a threat. While some saw the colonies as an opportunity merely to dissent from the established church, the Quakers saw an opportunity for martyrdom, preferring “to die for the whole truth rather than live with a half-truth.” Because Rhode Island declined to persecute them, they avoided that colony and instead immigrated to Massachusetts where expulsion, flogging, and torture awaited them. “Never before perhaps have people gone to such trouble or traveled so far for the joys of suffering for their Lord.” The perception of menace led to increasingly brutal forms of persecution; in 1658 the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted a law prescribing the death penalty for Quakers.[2]

Richard Swain was born in Berkshire, England about 1595, and came to Newbury, Massachusetts bay with his wife Basil (yes, an unusual name) in 1635. In 1638, he was among a group of petitioners who were granted the right to create a settlement in what we now call Hampton, New Hampshire—then part of the Massachusetts Bay colony—where he was granted 100 acres of land. Six years later, he petitioned and was granted 30 acres in the new settlement of Exeter. He was a member of the church and a respectable citizen, holding several offices, including selectman, and owning several properties. In 1657, his wife Basil, died. Shortly thereafter, a George Bunker* died, leaving his widow, Jane Elizabeth Godfrey Bunker*, with five children ranging in age from two to twelve. Richard married Jane, 30 years younger than him, in 1658. (Quick remarriage was encouraged, even enforced, in the New England colonies, so that indigent widows and their families did not become a burden on the community.) Richard and Jane had one child of their own, named after the father.

On 12 November 1659, Richard was convicted of “entertaining the Quakers,” fined 3 english pounds (about half the price of an ox in those days) and “disenfranchised”—losing his rights as a church member and citizen. We don’t know the details of his offense, but in a similar case, Thomas Macy simply had allowed Quaker travelers to shelter in his home during a severe storm.[3]

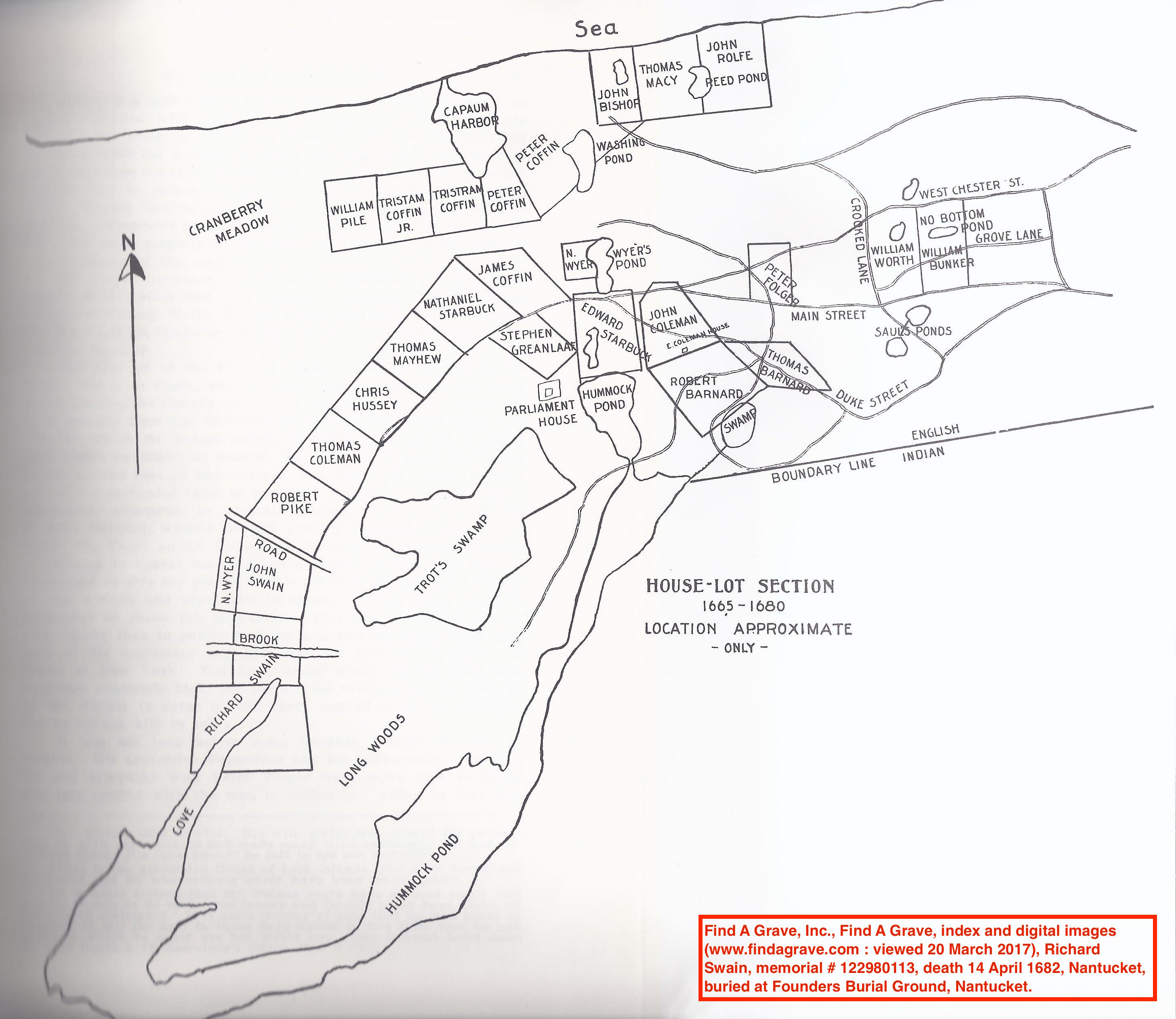

Swain was hard-nosed character. He reacted by joining nine (eventually 31) other persons, including Macy, to purchase nearly all of Nantucket Island from Thomas Mayhew* (who also owned Martha’s Vineyard). Nantucket was an attractive destination because it was, at that time, part of England’s claim to New York, hence beyond the jurisdiction of the Puritan Massachusetts Bay courts.

In a flurry of activity, Swain sold most of his properties, giving the remainder to his sons and the husbands of his daughters, leaving one son-in-law as his “attorney” to clean up his affairs in Massachusetts Bay. In 1661, along with 2nd wife Jane, her children, and one son by his prior marriage, he emigrated to Nantucket.

By 1664 he was the highway surveyor in Nantucket. By 1676, he had accumulated enough land to give Nantucket farms to his sons, Richard and John, and to Thomas Look*, the husband of his wife’s daughter, Elizabeth*. He died in 1682 and is marked in the Founder’s Burial Ground in Nantucket.

Some sources uncritically claim that Swain and the other Nantucket immigrants were Quakers. This seems unlikely. Macy is known to have remained a Baptist until his death.[3] There was no Quaker “meeting” (their word for congregation) on Nantucket until 1708.[4] It seems far more likely that they were simply escaping an oppressive government.

In the 18th century, Nantucket became almost completely Quaker and began its domination of the commercial whaling industry. Most of the whaler owners and captains were Quaker.

- - -

* Thomas and Elizabeth Bunker Look are 8th great-grandparents of the Moore brothers, so George and Jane Bunker (her first marriage) are 9th great-grandparents. (Thomas Macy’s daughter, Mary, married William Bunker, another child of Jane’s first marriage.)

Thomas Mayhew (the lord of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket) is a 9th great-grandfather along a different line. I have described his life in another story.

- - -

Except as otherwise noted, this article is based on:

Robert Charles Anderson, The Great Migration: Immigrants to New England 1634-1635, 7 volumes (Boston: New England Historical Genealogical Society, 1999-2011), vol 6, pp 609-617; indexed database of page images, NEHGS, AmericanAncestors.org (https://www.americanancestors.org/DB397/i/12124/613/147531186 : viewed 18 March 2017); genealogical biography of Richard Swain.

Other sources:

[1] “George Fox”, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., Wikipedia.org (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Fox : viewed 27 Mar 2017).

[2] Daniel J. Boorstin, The Discoverers: The Colonial Experience, (New York: Vintage Books of Random House, 1958), pp. 36-38.

[3] "The Macy-Colby House: Amesbury, Massachusetts," (http://www.macycolbyhouse.org/Thomas-Macy/ : viewed 27 Mar 2017).

[4] “Frequently Asked Questions: Quakerism in Early Nantucket,” (https://www.nha.org/library/faq/quakers.html : viewed 27 Mar 2017).