It was March of 1886 in Henley, Oxfordshire and Christopher Lardner was facing a dilemma. The final obstacle to his marriage to Lydia Busby was to provide information required by the Church of England. (Never mind that they were marrying in a “Protestant Dissenter” church.) If he gave truthful information, the marriage might be off. The problem was the name of his father, a name that didn’t match his own.

The 1871 census of England recorded Christopher as a 10-year-old “inmate” of the Witney Union Workhouse, a poorhouse established to serve the needs of a portion of Oxfordshire. Within the workhouse, the adults were segregated by sex and separated from their children. Families might visit once a week or so. The census, though, reveals no other Lardners resident in the workhouse at the time.

By the age of 20, young Christopher had found a job outside the workhouse, as an ostler, a person who handles the horses of visitors to an inn or a tavern. He boarded with a family named Dykes in Brentford, Middlesex (now part of greater London). The economy was good and, by the time of his engagement, he worked as a railway porter at the Victoria Dock. Because he lacked other family, Mrs Dykes stood for him at the wedding.

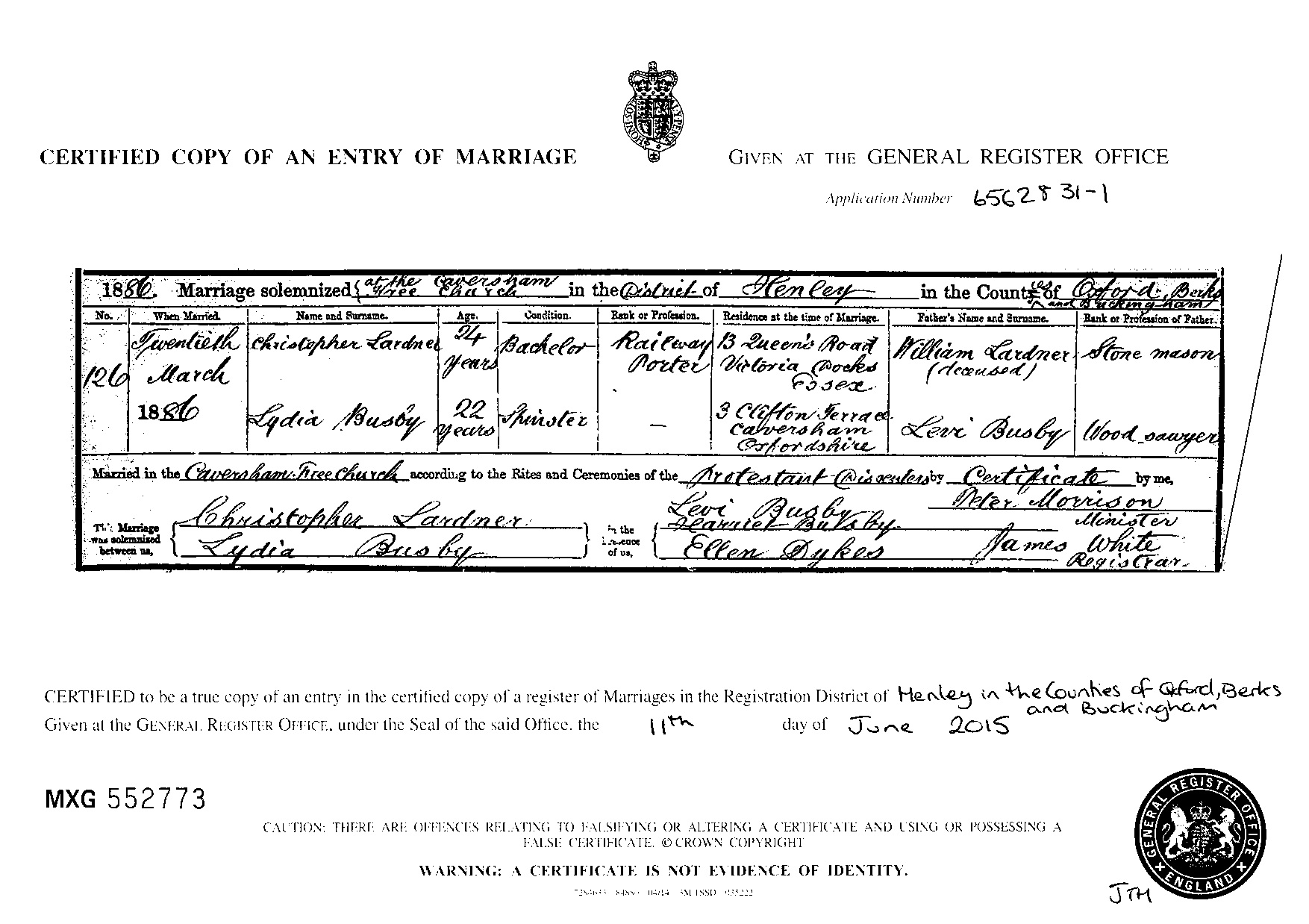

As Christopher considered the required information, he did what many other young men did in his situation. For his father’s family name, he gave his own. For his father’s given name, he picked a common one, William. He listed the occupation as “stonemason” and added in parentheses “deceased”.

Christopher and Lydia married and produced three children, two of whom, a boy and a girl, survived beyond infancy. Christopher died in 1899. Lydia remarried; the family emigrated to New York, via Ellis Island, in 1903.

But who was Christopher’s father? Thanks to a peculiar Victorian custom, we know the answer to that question. A child born out of wedlock is given, of course, the mother’s family name. For the given name, according to custom of the times, the mother usually chose that of a sibling or friend of the father—a remembrance without obligation.

“Christopher” is an uncommon name. A search of census records finds a Christopher Buckingham living in Oxfordshire. He had a brother, James, who in the 1861 census was listed as "head" of household with an Ann Lardner as a ”servant”, both unmarried. Her two children were also resident. Both of them and a third about to be born, our Christopher, had names matching James's siblings.

And, as you might have guessed, both Buckinghams were stonemasons.

Christopher Lardner was a great-grandfather of the Lardner sisters.