Thomas Haywood looked across the sights of his rifle, wondering how a mere 100 men would be able to defend themselves from the approaching landing parties of 80 British warships anchored a few hundreds yards away.

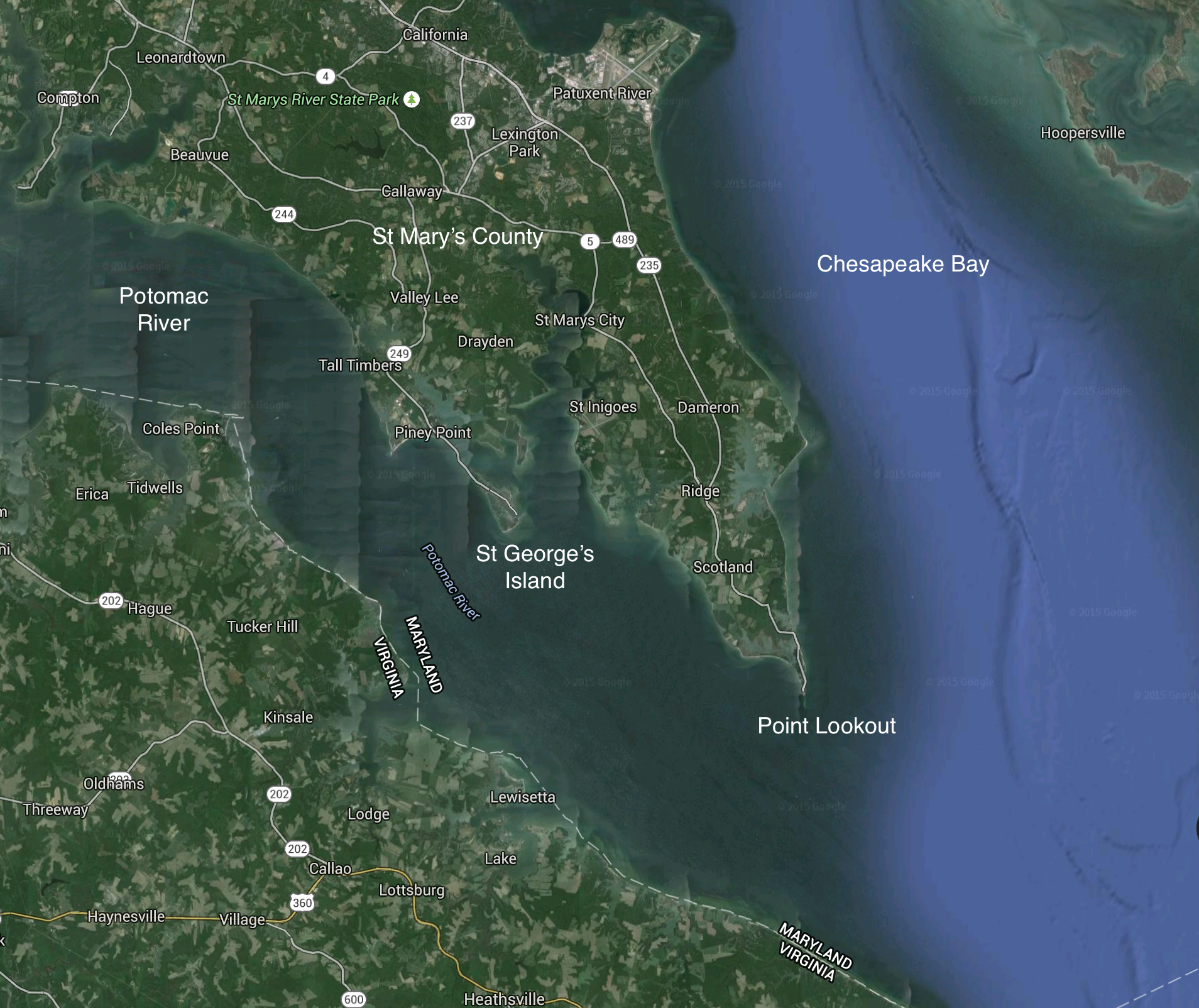

Thomas Haywood was born in 1756 in St Mary’s County, MD. That’s the Maryland “Western Shore,” the peninsula that separates the Potomac River from the Chesapeake Bay. His life might have been ordinary except that the American Revolution broke out during his 20th year; he enrolled in the militia. The Maryland militia had been training for a year when the war began, so were better trained and more disciplined than many.

Warnings arrived on July 12, 1776 that Lord Dunmore’s fleet had entered the Chesapeake Bay: “forty sail of square rigged vessels are as far up the Bay as Point Lookout,” the tip of the peninsula. Five companies of Maryland militia were ordered there to prevent a landing. Two small boats rowed from the fleet to the shore and politely advised the militia’s officers that the force intended to take St George’s Island the next day.

On July 17, Capt Rezin Beall deployed his 100 men in a thin line concealed by bushes along the coast of the island. They watched as each ship filled a boat with armed men who began rowing toward the shore. Beall ordered his men to withhold fire until landing parties were within 25 yards. The men followed his order with precision. The abrupt salvo of his militia came as such a surprise that the landing parties were thrown into confusion and withdrew to the fleet. The fleet returned fire with naval cannon, wounding a number of men, including Beall. Nevertheless, the fleet left without further consequence. 100 militia had repulsed 80 ships!

Some historians have discounted the intended landing as a simple foray for wood and water. In the War of 1812, though, the British succeeded in a similar landing and plundered Maryland.

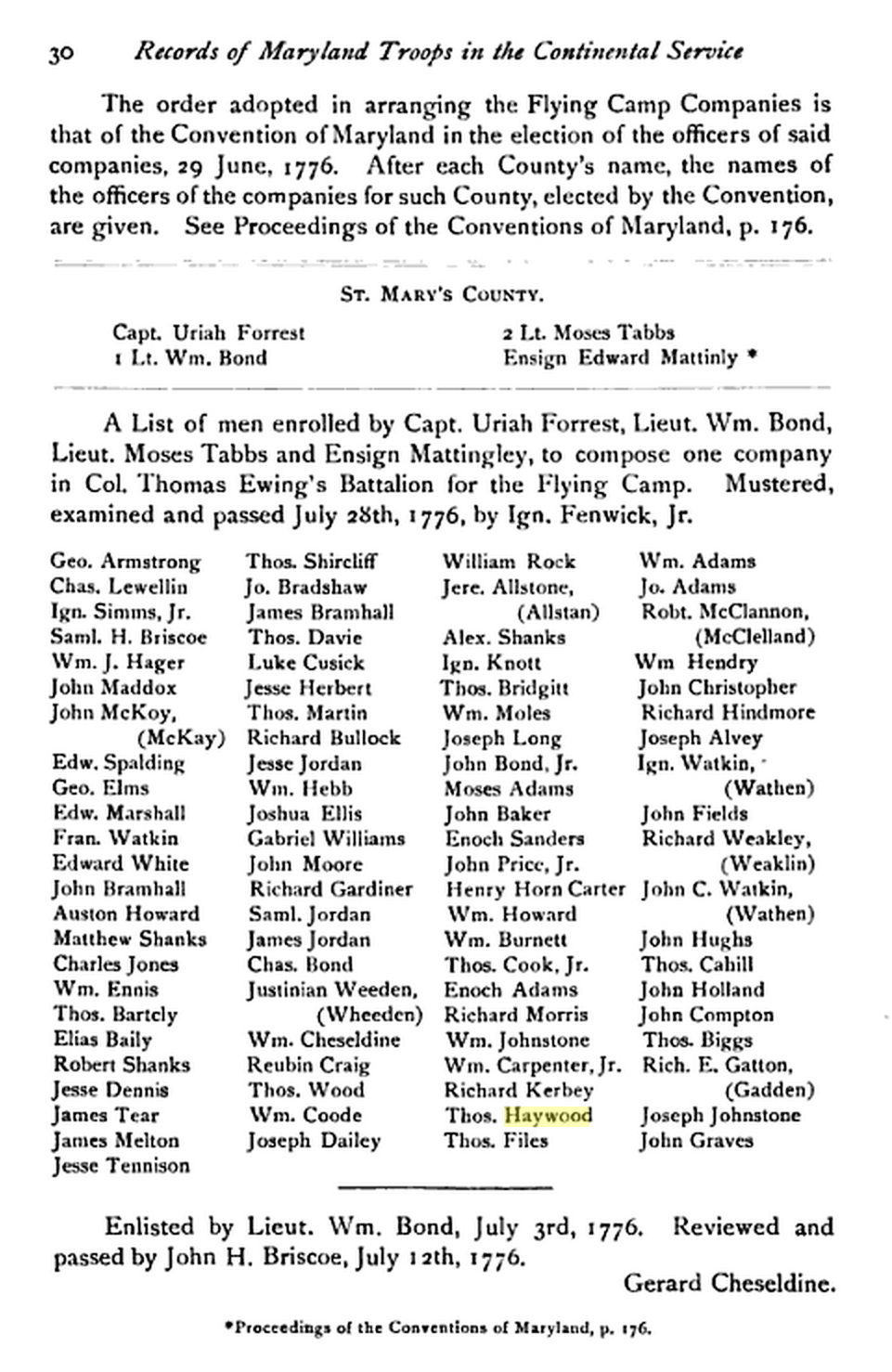

Later in July, militia units from Maryland, Delaware and Pennsylvania, were reformed into George Washington’s “Flying Camp.” The Flying Camp, intended to number 10,000 men, was not to be commanded locally like other militia units. Instead, it was to be used as the strategic reserve of Washington’s new army. Thomas Haywood was a private in Capt. Uriah Forrest’s company of Col. Thomas Ewing’s Regiment of the “Flying Camp.”

The Maryland militia went on to distinguish itself in the Battle of Long Island, the Battle of White Plains, and, eventually, even in the Carolina campaign. George Washington called them his “Old Line”, giving Maryland its nickname.

Thomas Haywood survived the War. (That’s fortunate for the Moore brothers, because Thomas is their fifth great-grandfather.) In 1781, he married Mary Shermantine. An 1832 resolution of the Maryland General Assembly granted him a pension and he died peacefully in 1845.

Thomas and Mary’s son, Joseph Haywood, fought in the War of 1812, but that’s another story . . .

The primary source for the account of the St George’s Island landing is: Reno, Linda and White, Greg, “From Obscurity to Greatness, the Story of Uriah Forrest,” http://userpages.umbc.edu/~pdavis2/Participants/dawsonm/smc/articles_files/june04_Forrest.htm, 13 June 2004. Linda Reno is also the source for the genealogical information of Thomas Haywood.